In the early 1990s, e-mail was spreading like wildfire. Among its early adopters, the most religious ones were from the academic community. In 1997, John Sutherland 1wrote that then an “e-mail address was for professors what the cellular phone was for their students: a sign that they were ahead of the game.”2.

These days, in 2021, and as far as tech gadgets possessed as signals of status and progressiveness go, Sutherland’s comparison remains valid if we replace cellular phones by an Apple iPhone, and e-mail by a blog or personal website.

In an essay he published in The Guardian (which is by now removed from their website, following a massive Twitter campaign against the novelist mainly because of his opinion on techno-consumerism), titled “What’s Wrong with the Modern World?”, American novelist Jonathan Franzen wrote:

“Isn’t the essence of the Apple product that you achieve coolness simply by virtue of owning it? It doesn’t even matter what you’re creating on your Mac Air. Simply using a Mac Air, experiencing the elegant design of its hardware and software, is a pleasure in itself, like walking down a street in Paris. Whereas, when you’re working on some clunky, utilitarian PC, the only thing to enjoy is the quality of your work itself.”

Franzen, like Karl Kraus3‘s dichotomy between Romantic and Germanic cultures, presents us the “Mac versus PC” dichotomy, and like Kraus before him he chooses content over form. “I’d still rather live among PCs” he wrote.

When Philip Roth said that “the novel’s day has come and gone” many members of the literati thought he is yet another anti-tech novelist opening up about his distaste for the age of screens. Literature “is one of the great lost human causes” Roth said, “Oh I don’t think in twenty or twenty five years people will read these things [books] at all”4 And when Jonathan Franzen dubbed Twitter as “dumb”, writers and Twitter users alike tweet-stormed him in an outrage.5 Yet these critics of Roth and Franzen, and who couldn’t relate to neither the former’s austere lifestyle, nor to the latter’s obsession for watching birds, are now willing to spend up to five hundred dollars for smart typewriters, like Astrohaus’ Freewrite Traveler, so they can write without any distraction.

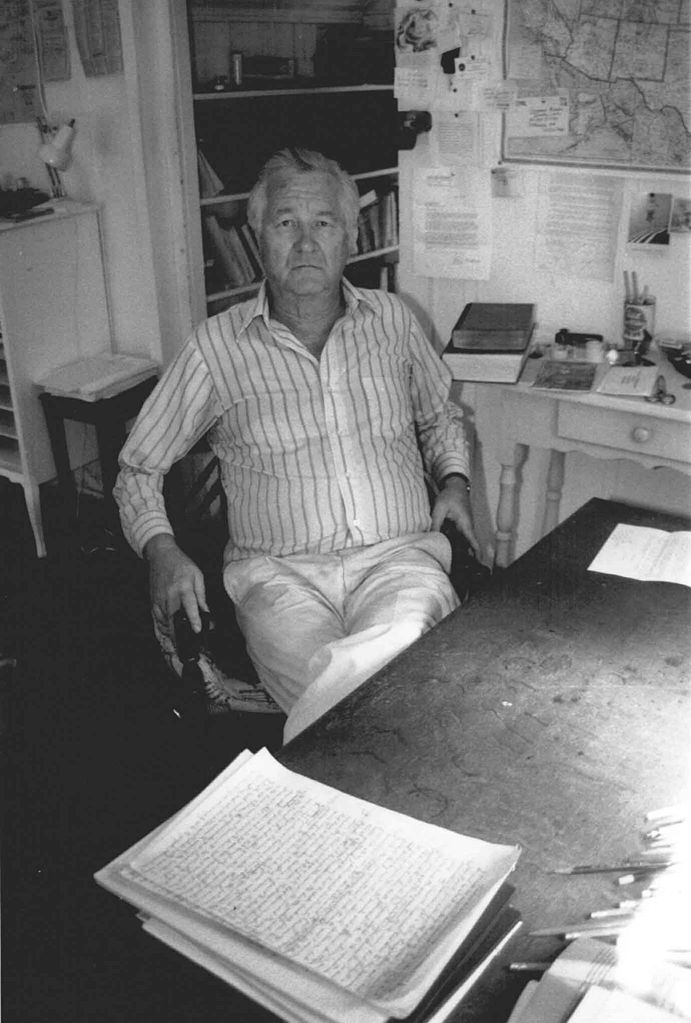

Not all book worms are as pessimists about the future of books and reading as Philip Roth. The German writer Günter Grass6, whom Mario Vargas Llosa7 described as “one of the most significant writers of the 20th century”8, had always believed in the private intimate connection with a book. During the 2001’s World Book Day celebrations in Berlin, and when asked about how he sees the future of books, Grass said:

“There is no surrogate for books. The act of reading, the private company of a book which you can carry around, to the loo, to your bed, on your travels—no computer can replace that. This intimacy provided by reading is irreplaceable. In many respects, I am a pessimist, but as far as books are concerned, I am sure they will survive.”

Günter Grass 9

More than fifty years ago, on September 2nd 1969, an experiment at a UCLA lab had been conducted “to watch two computers transmit data from one to the other through a 15-foot cable”. Three months later, four nodes of the new “packet switching” network, then named, ARPANET “were up and running.” ARPANET was named after the US government’s defense agency department, which “conceived and paid” for it. ARPANET later became DARPA—the “D” stands for Defense.

Technically, the internet as we now know it “was born when ARPANET was converted to TCP/IP in 1983.” Eight years later, Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Caillian, of the European Center for Nuclear Research, invented the World Wide web.10

Recent official reports about internet usage from governments worldwide are alarming. In Malaysia, a country of 32 million people11, 88.7% was the percentage of internet users in 2020. More than a quarter of them have been using the internet for more than a decade as of 2020. Half of them spend “5 to 12 hours a day on the Internet”, while 21% spend more than 12 hours a day on the Internet.12

I don’t blame people who read paperbacks and hardcovers instead of PDFs and Epubs anymore. I myself have tried a similar experiment: instead of consuming PDFs, I print them, and actively read them (taking notes while thinking about the material). As a result, I was able to concentrate for longer blocks of time, read more, and grasp more; however, like any first act of rebel against an addiction, I was met with withdrawal symptoms, mainly the urge to open the laptop, and search for something on Google.

How can we gain back our ability to focus? Is there anything that can be done to reverse the damage our brains has accrued since they had been stuck to the internet?

The fact that Astrohaus had sold out its Freewrite Traveler model of its smart typewriters is nothing but a proof for Roth, Franzen, and Günter Grass’s case, that computers and the internet are only tools in the writing process, and that an anti-tech attitude is sometimes necessary for those who only can get things done when they get tough on themselves. The British journalist Kirsty Wark was once shocked at Philip Roth’s daily routine and lifestyle, and how much loneliness he could endure; Roth explained “That’s the only way I could get my work done.”13

For Franzen, the only way to get his work done is to not to have any access to the internet. His ten rules for writing has gained him a group of fans and haters; specifically the “I doubt that anyone with an internet connection is writing good fiction” rule. I myself couldn’t see why people would disagree with this one rule. Most people would agree that leaving the internet open while writing is, for many (if not most of us) is like writing in front of a window. In fact, it is a digital window to a world wide web, where access to information is instant and free, and where notifications and apps only intensify the lack of focus, and impulsivity, and the curiosity to google that thing. In his 2006 introduction to On Writing Well, American author William Zinsser wrote: “I don’t know what still newer marvels will make writing twice as easy in the next 30 years. But I do know they won’t make writing twice as good.”14

On the one hand, I resonate with Franzen’s take on the internet, and on corporations, yet on the other hand, I can’t deny that for someone like me, a marginalized North African kid whose first interaction with any part of the internet dates back to circa 2005, the internet was the only way I could’ve accessed the body of knowledge that could fulfill my curiosity, and my eternal search for a way out of the “shithole”. Without the internet, I would have been a very different man. Without it, I would have succumbed to all the currents of local nationalism, religious fanaticism, and the currents of elite leftists running the “shithole” and confining everyone with them in eternal misery.

Perhaps, the first step is becoming conscious. Consciousness about how much time are we spending emailing and texting, listening and watching, filling forms and closing popup ads. When we track the hours, we become shocked—not at the numbers per see—at what could have been learned, grasped, or done during these wasted hours.

After consciousness about the amount of time we waste online, the next move is to transition towards being a pragmatic user of the internet. This might not work for everyone, but becoming pragmatic users means planning our online tasks before we even open the internet—that’s how serious we must become towards the addiction: treat it as an addiction, a serious threat to our minds and to our lives. And we should forget about throwing our phones, deleting all of our accounts, and isolating ourselves from the rest of the digital world, all at once. Almost all cold turkey attempts to break free from internet addiction have failed, and ours will probably fail too. Instead, we should progressively attempt to limit and plan the time we spend online—in advance.

“A restlessness has seized hold of many of us,” wrote the American author Rebecca Solnit, “a sense that we should be doing something else, no matter what we are doing”.15 It’s the same restlessness that reminded Franzen of “what Marx famously identified as the ‘restless’ nature of capitalism.”

Personally I’d been deprived of access to computers and the internet for several straight months. It was a tough experience—not by choice, but by obligation. Going months straight without access to the internet forced me to go slower, to think deeper, to concentrate better, to make rational choices, and to prepare better plans. Not to mention the discipline to have a routine that works for me, not to jump into using electronics first thing in the morning, and instead, do the sort of things that propel me to get my work done early during the day. It also taught me not to skim through PDFs—and instead read them, and take detailed notes of the material I read. These notes have accumulated into an archive of my notes; it is one of my most valuable assets.

I think that all it takes to realize the dangers of internet addiction is to watch people around you. Watch how they hold their phones, how they look at their screens, how they scroll down through their feeds, how they jump into watching random stories and videos. If these people are close enough to you, you will begin to notice the influence of their digital habits on their self-image, their life choices, and their goals.

I sometimes wonder what will happen if the internet gets suddenly shut down worldwide? Will hundreds of millions of internet addicts go down the streets protesting, and possibly overthrowing their governments?

The way I see it now, is that the excess of these “informational floods” will only make the top one percent shrink in numbers, and grow in assets owned. For those in the Bottom Billion, most people won’t use the internet to climb the socioeconomic ladder; the amount of stories and “TikTok influencers” occupying their time and attentions won’t leave them a moment for that.

That’s the paradox: the internet is here thanks to governments. Its structure resembles a democracy—to some extent. Yet it is often threatened by governments (under totalitarian regimes), and indirectly leads to more inequality (as those who will reap its benefits are few individuals and corporations).

Instead of the slow and deep thinker that reading requires, the constant use of the Internet could turn one into a quick responder, an attendant who receives information and instantly demands more. Reading requires a genuine interest, a commitment of energy and cognitive capacity into the text at hand. When reading, one stops at the middle of a paragraph that has struck him, and think it through twice. The reader might even argue with the author, or even laugh at him and his superficiality. In short, voracious readers ultimately become critical thinkers. The Spanish essayist Miguel de Unamuno is attributed this quote: “Fascism is cured by reading, racism is cured by traveling.” I spent hours searching when or where did he say or wrote that to no avail. Whether it is Unamuno who wrote this or not, I am not sure about his latter claim, but I would like to think that the former is true.

Ben Wajdi’s Blog is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you can support my work by buying me a book (one time donation).

Footnotes

- British author and academic

- Sutherland, J. (27 November 1997), The Browse Function. London Review of Books, Vol. 19, No 23.

- Austrian satirist writer of the late 19th, and early 20th century.

- Brown, J. (c. 2004). Philip Roth (on Youtube). PBS NewsHours.

- Finch, C. (2016.). In defense of Jonathan Franzen – the internet’s collective punching bag. The Guardian.

- Günter Grass, a German novelist, and author of the Danzig Triology (The Tin Drum (1959), Cat and Mouse(1961), Dog Years (1963)) who received the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature. He wrote on his Olivetti typewriter until his old age, and never had a computer at his writing studio. He passed away in 2015.

- Peruvian writer and politician

- Grass changed the world of the novel says Mario Vargas Llosa

- Rediscovering the joy of reading, DW Germany

- The internet at forty, The Economist

- Demographic Statistics First Quarter 2020, Malaysia

- Internet Users Survey 2020, Malaysia

- Wark, K. (c. 2009). Philip Roth: ‘Work is my joy and my burden’ (on Youtube). BBC Newsnight Archive

- Zinsser, W. (c. 2006), On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing.

- Solnit, R., In the Day of the Postman (2013), LRB