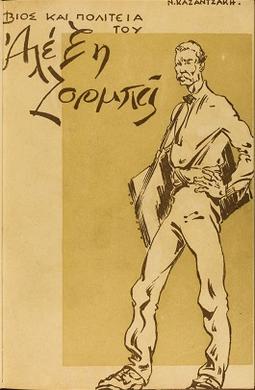

Zorba the Greek

By Nikos Kazantzakis, Translated by Peter Bien

Simon & Schuster, 368 pp., December 2014, 978-1476782812

Paperback (Amazon) | Paperback (Bookshop) | Audiobook

Nikos Kazantzakis classified Alexis Zorba, along with three other individuals, as the only ones who “did engrave their traces most deeply upon [his] soul”. The others are: Homer, Bergson, and Nietzsche.

The novel starts with a prologue in which the author gives us a background of his real life encounter with the person upon whom the character of Zorba is based. The novel is Kazantzakis’s trial to immortalize Zorba and their whole encounter. They first met in a café, at dawn, in Piraeus, Greece. Zorba convinced the narrator to let him be his worker in the lignite mine, and his companion in the journey.

Alexis Zorba—whose nicknames include “Grapevine”, “Roarergazorer”, and “Mildew Fungus”—is an old Macedonian miner from a village at “the foot of Mount Olympus” and had tried all the trades and all the jobs (including a peddler touring Macedonian villages selling what he could get his hands on for “cheese, wool, butter, rabbits, or sweet corn”), who plays the Santouri and dances the Zeibekiko, the hasapiko, and the Pentozali.

Once, when he was a potter, he cut his left hand’s forefinger short because it kept interfering and “hindered [him]” in his work. A complete devotion to the task at hand is one of Zorba’s strong traits. “One thing at a time in proper order. Right now we’ve got pilaf in front of us; let our minds be pilaf. Tomorrow we’ll have lignite in front of us, so let our minds, then, be lignite” said Zorba to the narrator.

From the beginnings, we can feel that the character of Zorba had left an immense effect upon the narrator, who portrays him as “a laborer of advanced age whom I exceedingly loved.”

At one point, Kazantzakis even confessed to his own cowardice saying that the old man “possessed precisely what a pen pusher [like the narrator] needs for deliverance.” He often found himself standing before Zorba, admiring him—while shaming himself—for the youthfulness of his soul, for his vibrant energy, for his unique life experiences, and for his gut, his courage to dare “do what supreme folly—life’s essence—was calling [him] to do.”

So far as I know, Your Excellency has never gone hungry, never killed, never stolen, never committed adultery. So, what can you know about the world? Immature mind, inexperienced body,alexis Zorba

Zorba, a Macedonian who fought in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, who killed, raped, slaughtered man for Crete, for Greece, and for Prince George—while at the same time despising wars—loves everything Cretan. He can’t neither stand nor understand our need for the dogmas of nationalism and religion; two forces, when blend together in a moment of ignorance, are capable of transforming one into a raging lunatic, who, in Zorba’s words, pounces “on another human being who has done nothing to you and bite him, cut his nose, help yourself to his ear, and tear open his belly while calling upon God to come down and help you”.

Reading the translator’s introduction, I saw Bien‘s hard work to render this newer edition of Zorba the Greek the best and most accurate English translation of Kazantzakis‘s masterpiece on the market to date.

I discovered too, much to my surprise, that some Cretan words (not available in traditional dictionaries, and which the translator put extra effort to decipher) were words I was used to, and which I heard as a kid in North African Tunisia. One of these words is “Aman!”, meaning please in a begging tone, often indicating that you are either requesting something from a superior subject, or used in pejorative way while defending yourself within a conversation. This, perhaps, reminds me of how much we—people of the Mediterranean, on both sides of its coasts—have in common; including own slower life than our American counterparts, the way we talk about or handle wine and olive oil—there are two sacred staples in any true Mediterranean table, and finally our life-long obsession with form over essence, looks over substance, the immediate now over the mysterious tomorrow.

Zorba and the narrator arrived in Crete. They lodged at an old hotel owned and managed by an old French woman, Madame Hortense. The property “consisted of a row of age-old bathing cabins glued together one behind the other”, and smelled of pungent urine.

Madame Hortense is a “fallen woman,” the narrator and Alexis Zorba “had met on a sandy Cretan beach by the Libyan Sea.”

To prolong one’s parting from a beloved friend is poison. To leave with a knife stroke is better, for it allows one to return to humanity’s natural climate: solitude.

The unnamed narrator, who we know is Cretan, is oversensitive towards all Cretan scenery and smells. A naturalist at heart, with an unconscious awe reaction towards Cretan natural beauties.

There is this contrast between the characters of Zorba and the narrator, how much differences between them, yet how compatible they are, throughout their Cretan journey, and beyond. The narrator who is lost in books and youthful idealism, who believes in equality and want to open the eyes of masses to the the truth, while Zorba, an old Macedonian fellow enlightened by action and travel rather than theories and books, and who would rather keep the masses’ eyes blind to the truth than open them. “All right, go and open Uncle Anagnostis’s eyes for him. Did you notice how his wife stood there cringing and awaiting orders? Well, Your Highness, how about going now and teaching them something about women, that they have the same rights as men and that it’s truly a mean thing to a eat a piece of a hog’s flesh with the hog alive, bellowing in front of you,” said Zorba to the narrator.

Even after their separation, each one of them had the other’s essence within him; the narrator had an everlasting Zorba that could neither be erased, nor forgotten from his memory and soul. Zorba too never forgotten his young Cretan friend, he sent him a telegram amidst starving and difficult times demanding that he should come visit him, and see “the best green stone ever”.

The narrator, who just like Kazantzakis interacted with his friends and relatives by exchanging letters with them, first received a letter while he was in Iraklio, going back to Athens after his journey with Zorba had come to an end, and after their lignite mining project collapsed along with Zorba’s aerial runaway innovative technology to the ground, notifying him of the death of his long time friend Stravridakis. Twenty years or so later—if we assume that the timeline of events in the novel follows the same timeline of the real encounter between Kazantzakis and George Zorbas (the real life miner on whom Alexis Zorba’s character is based)—and after finishing writing the Zorba manuscript, the narrator received a letter from Skopia, Serbia informing him that Zorba passed away, and his final words were “People like me should live a thousand years. Good night:”

Kazantzakis began writing the novel in 1941 (during the Nazi occupation of Greece) in the island of Aegina. His wife, Eleni N. Kazantzakis wrote: “on the darkest days of starvation, Nikos penned his most joyous work: Zorba the Greek!”

The novelist himself, and in a letter he sent to his friend on 22 August 1941, wrote: “I cannot find work, no one will stage my plays, and my financial situation is absolutely critical”.

Writers can never anticipate or predict the impact of their work into the future. Even, the urge to write itself, and why we do it is still a mystery. Nikos Kazantzakis too couldn’t expect that the manuscript he had written while he had been at the edge of starving would be read by millions worldwide, summarized, analyzed and studied in literary courses, and that the phrase “Zorba the Greek” becomes a brand name for nine restaurants worldwide promoting the Mediterranean diet; one in Singapore, one in England, five in the United Stated, and one in Brasov, Romania.